u Princeton, NJ. | Monday, December 2nd, 2014.

Princeton, NJ. | Monday, December 2nd, 2014.

Dear Photographer Pablo Ortiz Monasterio,

I was fortunate to attend your lecture “Mexican Portraits” at Princeton University last Monday. Part of me wished you were one of the speakers during the symposium Itinerant Languages of Photography organized by Princeton’s Spanish and Portuguese Department. Although you didn’t speak during those 3 days, your presence was felt. Your work was well represented in the exhibition and book with the same title. The words during your lecture were so soothing to me. Reading from the pages of your own books, you told us: a photograph is powerful. Not once upon a time, but today, during a time, when all we hear about is the silencing of images happening by their mere volume. There are too many images. There are cameras everywhere. Everyone is a photographer. But you whispered: images still have a voice. Maybe not in the promiscuous space of the internet, where photographs are posted, blogged, twitted and constantly reproduced out of context. But they have a voice loud and clear inside books. For sure, inside your books. Once incorporated into a page, a photograph is protected by a defined space. Separated. Individualized. Your words gave photography a skin. Book pages are like membranes. A contamination happens from within. The meaning of one image transmitted to the one that follows, and vice-versa. In pairs, images carry meanings previously nonexistent, but surely present as a double.

You reminded me I don’t want every one of my photographs spilled immediately into a Flickr-Instagram-Pinterest-ocean. But instead, I want my images to be edited, selected, sequenced, interpreted, so my work in photography can be purposefully and intentionally written. Maybe this way, we wouldn’t be destroyed in a “tsunami of images”, like Joan Fontcuberta told us. A volume of images that makes us dismiss, ignore, reject and discard images, no matter how relevant or powerful those images are. Take Susan Meisellas’ ebook Chile from within, for example. How come, everyone is not downloading this book? Not only a testament to a time when photographers tiptoed respectfully into the editing process; Walking barefooted among photographs carefully printed from hand-picked negatives; But a statement to the powerful process of creating and sharing images among fellow photographers, working for weeks, to read and write photography collectively.

Which is why I am grateful to Gabriela Nouzeilles and Eduardo Cadava for organizing, curating, and generously hosting “Itinerant Languages of Photography”. The book, exhibition and symposium gave photography a space. We read photography. We discussed photography. We looked at photography. Once again, Photography was observed, described and interpreted. Sometimes by scholars like Geoffrey Barchen illustrating a history imprinted with photographs; or by Professor Maurício Lissovsky, and his observations on the Greeks’ concern over the effects the written word would have on rhetoric. A lyric reminder that trivializes the current digital versus analog debate. But throughout the symposium photographers themselves stepped into the stage. They carried with them a questioning that sometimes can only be detected by a fellow artist’s eyes. The photographer is exposing himself. Depicting himself. Exhuming his own body of work right there on stage. And this questioning is always followed by an internal knowing: Art is never easy; It is challenging to create it; It is daring to present it; It is daunting to interpret it.

There is a kind of teaching that only comes from a fellow artist. At your lecture on Monday, or during the symposium, I was transported to a time when I’ve learned directly from other artists. A time when I was a student at Escola Guignard. An art school in Belo Horizonte, Brazil that throughout its history tried to balance the roots set by its founder and the demands of higher education. From the painter Guignard’s perspective, the lessons came as much from nature as from another artist. Guignard’s students became my teachers. Other artists also came and taught. Art was passed from artist to artist. Degrees and diplomas were a mere consequence.

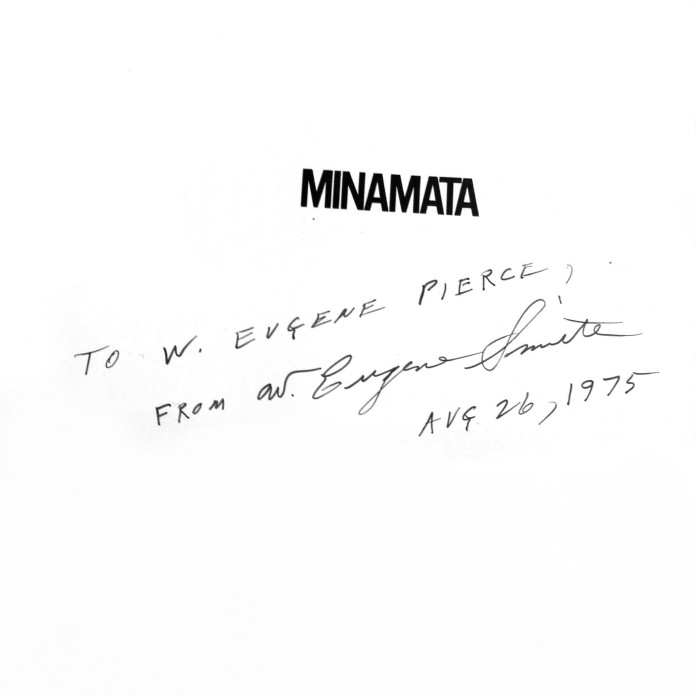

For my husband, photographer Eugene Pierce, learning wasn’t much different. Some of his most memorable lessons also came from an artist. Gene was named after a family friend. This man was a frequent guest. He lived in and out of the darkroom that existed in the house. A kid less than 10, Gene was lured into that room. His curious observations as a child were not only acknowledged by this photographer, but were fed by him. Among negatives and prints; Among images and war; there was this man. A man wounded in war. A man with not enough time to document events like he wanted. Not enough money to support family or craft. Struggling but still producing images, still producing photographs, still being a photographer.

After listening to the Symposium’s closing remarks, Gene and I sat at a coffee shop, and we had a catharsis of what we’ve just heard. Photography might not be dead, but it had been distorted, manipulated, infringed, reappropriated, to the point of becoming unrecognizable. And we felt impotent. There was a tsunami coming. A tsunami of images. How could we be heard? Like our voices muffled inside that cafe, our photography was disappearing. Gene still believes in the power of portraiture; in printing. I still believe in the power of the essay; in narrative. What can we do about it? We can’t change this. We can’t stop these tendencies that are seeping into every corner of this profession. The lack of skills. The trickery of effects. The false promises of technology. The indifference to the moment. We are sitting here, watching the death of a craft in an instant. And we feel paralyzed.

But this disempowerment only lingers until we walk into a museum; and we stare at a black and white print; and we become speechless in front of the beauty of a Graciela Iturbide’s photograph. Until we face the photo of a tortured man on the wall, just to realize he is not only photographer Marcelo Brodsky’s brother, but our own brother. Until we look at a photo of the streets in Buenos Aires to find layers of interpretation intentionally embedded by photographer Eduardo Gil. Until we see through the transparent work and soul of Salvatore Puglia. A gentle and humble artist that spoke of his work during the symposium, even thought he didn’t have to. His work alone said it all. Until I held your book La Ultima Ciudad, Pablo. And I am transported into a city. Mexico City. Carried there to roam its streets. In moments like these, we remember how loud of a voice photography has.

Sitting at that cafe that evening Gene and I started to gather our thoughts and strengths. Maybe we could fight this force. We could use the weight of our opponent, as if photography is some kind of martial art. And we committed right there and then to Gene’s out-loud-thoughts: “I just have to continue this profession.” As he said it, I could only think of what it took to become a photographer; How daring it is be a photographer; How daunting it is to continue to be a photographer. And most of all, that a photographer is not a brief self-pronounced-tittle, but a perpetual self-developed-skill.

Pablo Ortiz Monasterio, I thank you for your teachings. For passing your craft from an artist to the next. I hope this cycle continues. That artists can teach others, like I once was taught by Guignard’s disciples, and Gene was once exposed to a craft by W.Eugene Smith.

With much gratitude,

Jennifer Cabral-Pierce